It’s not often that we recommend indulging in a “touristy” activity; we love the more hidden and authentic side of Italy, and personalized, local experiences that often aren’t accessible to mass tourism. There is one important exception to this bias, however: a ride in one of Venice’s iconic gondolas.

(Photo by Concierge in Umbria via Flickr)

As we said in our 48 Hours in Venice guide, “You wouldn’t visit Paris and skip the Eiffel Tower. You wouldn’t visit India and neglect the Taj Mahal. So how could you possibly not indulge in the most iconic of activities in Venice?” Part of this recommendation is based on the pure joy of floating down Venice’s picturesque canals in your private luxury sedan of the sea, but part of it is also because the gondola may have become primarily a tourist attraction over the past century, but for most of the last millennium, it was a fundamental part of Venice’s culture and daily life.

(Photo by Concierge in Umbria via Flickr)

The gondola dates back to the 11th century, and at the height of Venice’s wealth and power in the 16th-century, more than 10,000 gondolas crowded the waters of Venice. Some were used as simple shuttles transporting Venetians and goods through the city via water, owned by teams of four who rowed and managed the gondola, and some were elegant private crafts, owned by the many noble and wealthy families who resided in the sumptuous palazzi lining the canals.

(Photo by Concierge in Umbria via Flickr)

Today there are only a few hundred gondolas left in Venice, almost none of which are used as private transport by local Venetian families. Instead, they are almost exclusively a tourist attraction, but the gondola and the job of gondoliere is still deeply rooted in history and tradition, kept alive by the tourist trade.

The Gondola

Gondolas are still made by hand in one of the three remaining squeri (boatyards) in Venice. These squeri are generally closed to the public, but will open their doors to visitors if arranged in advance with a local guide. The most photogenic squero in the city is Squero San Trovaso, along the narrow Rio San Trovaso next to the Church of San Trovaso. The boatyard is easy to pick out: a group of Alpine-looking wooden boathouses right on the water, which has housed generations of the same family of artisans who have been crafting these wooden boats for centuries.

(Photo by Concierge in Umbria via Flickr)

It takes 40 to 45 working days to build a gondola, though the work done in squeri is primarily repairing and maintaining existing gondolas, and the cost of a new craft can be more than €20,000. Gondolas are made from eight different types of wood—mahogany, cherry, fir, walnut, oak, elm, larch, and lime—and have a shallow, flat bottom and asymmetrical shape, including a lower starboard side to compensate for the weight of the gondoliere who always rows from a standing position in the stern of the boat on the port side.

(Photo by Concierge in Umbria via Flickr)

The shape of the gondola has evolved over the centuries: the crafts historically had a lower prow, a higher ferro ornamento (see below), often a small cabin or awning to protect passengers from the cold or sun, and two gondolieri rowing. The modern gondola shape was developed in the 19th century, with continual tweaks until a law in the mid-20th century prohibited any further modifications.

Gondolas must be painted black by law, an ordinance which dates back to a 16th-century sumptuary law which tried to check the increasing gaudiness that had begun to touch all aspects of Venetian society, including their private boats. The boats also have a distinctive “forcola”, the complicated wooden oarlock which allows the gondoliere to hold the oar in several different positions, and “ferro”, the traditional ornamental symbol affixed to the bow made from brass, stainless steel, or aluminum which counterweights the gondoliere.

(Photo by Concierge in Umbria via Flickr)

The most recognizable part of the gondola is the intricate “ferro”, or prow decoration. It has a complicated symbolism, beginning with the “S” shape which represents the sinuous Canal Grande. The six teeth under the main blade symbolize Venice’s six “sestieri” neighborhoods, and the single tooth jutting out backwards, the island of Giudecca. The curved top signifies the traditional hat once worn by Venice’s “doge”, or governor, and the semi-circular break between the curved top and the six teeth symbolizes the Rialto Bridge. Some “ferri” also have three friezes between the six prongs, for the islands of Murano, Burano, and Torcello.

The Gondoliere

Just as the gondola is an iconic symbol of Venice, so too is the gondoliere, or the traditional oarsman – or, just over the past few years, oarswoman – who dons the black and white striped shirt and straw boater and steers sleek black gondole through the narrow canals and under the low bridges of Venice. Though it may look like the gondoliere is steering the craft with a pole like a punt, the city’s canals are much too deep for this; gondoliere use a single, long oar and row in a traditional style known as “voga”, a type of sculling which uses the oar to both propel and steer.

(Photo by Concierge in Umbria via Flickr)

It has always been extremely difficult to enter into the ranks of the gondolieri. Historically, a gondoliere license was passed from father to son, or other male relative if there was no male heir. Though licenses are no longer hereditary, all gondolieri must belong to the professional guild, which has a history stretching almost a millenium and strictly controls its membership. Only a limited number of licenses are issued, and these are only granted after an intense period of training and apprenticeship with an experienced gondoliere followed by a comprehensive exam. This exam not only covers practical skills in handling the gondola, but also Venetian history, landmarks and foreign language skills.

(Photo by Concierge in Umbria via Flickr)

In August 2010, history was made when Giorgia Boscolo became the first woman to complete the rigorous training and be granted a license from the Gondoliers’ Guild. Her father, a gondoliere himself, commented at the time that he wasn’t sure if it was a “suitable profession” for women, but since then the Guild has been more proactive in recruiting female gondolieri.

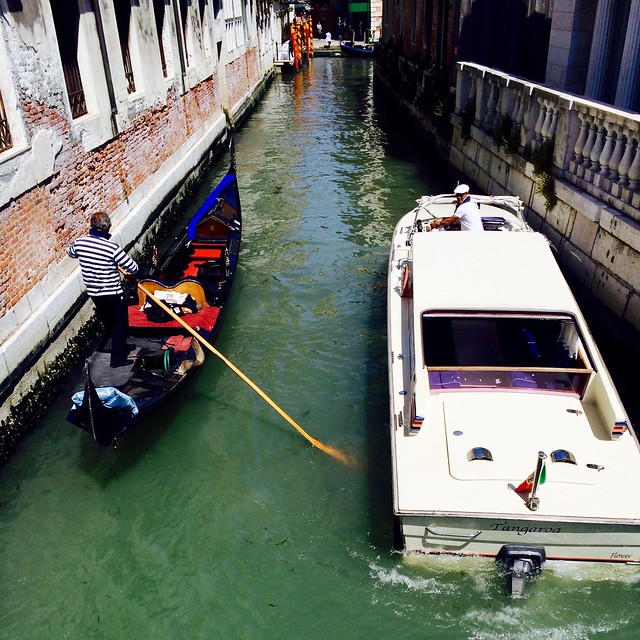

That said, navigating a gondola is much more physically demanding than it may seem. Though its flat bottom makes it very stable, its wood hull is extremely heavy. It takes both skill and strength to propel and steer with a single oar, navigating the busy waterways – now crowded with motorized craft – and narrow turns lined by buildings in the smaller secondary canals.

The Ride

Though we encourage you to splurge on a gondola ride while in Venice, we don’t mean you should blindly hop into the first craft you see.

(Photo by Concierge in Umbria via Flickr)

Make sure you carefully negotiate both price and length of your ride before getting in. The city rate starts at around €80 for around 40 minutes during the day, and €100 for around 40 minutes in the evening…but actual rates are often much higher. Negotiate, but also remember that rides are expensive for a reason: Venice is one of the most expensive cities in Europe, and purchasing and maintaining a gondola is pricey. Settle on a price, but don’t expect a bargain, especially in high season!

(Photo by Concierge in Umbria via Flickr)

A gondola can hold up to 6 passengers, so if you are traveling in a group, it makes sense to hire one together and split the cost. Also, not all gondolas follow the same route. If you want a trip down the stunning but bustling Grand Canal, pick up a gondola near the Rialto bridge. If you want a quieter, more romantic ride, begin from a side canal where you won’t be vying with motor boats and vaporetti for space.